Ovintiv ($OVV)

Undervalued, low-cost oil & gas producer with a catalyst

Low-cost North American oil & gas producer trading at a significant discount on an absolute and relative basis

Capital allocation framework and roll-off of hedges and legacy costs create catalyst for re-rating in 2022

Activist shareholder has forced overhaul of management and introduction of shareholder-friendly executive compensation program

On the 15th of February, I pitched Ovintiv Inc. (NYSE: OVV) to the student fund at my university (a stock pitch which I am glad to report was accepted). I wanted now to put in writing what my thoughts were at the time, so that I could later look back and assess my decision-making against the eventual outcome of the investment. Although the holding period of the fund is only until July, I thought it would be a useful learning exercise to review this in a few years.

Since I pitched Ovintiv to the fund, Russia has launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, an event that has significantly increased oil prices due to the ensuing sanctioning of Russian oil and gas by Western governments and corporations. This, of course, has caused the stocks of Ovintiv and other public energy companies to appreciate sharply, but was not an event on which my thesis relied.

Given the performance of the stock, I may be showing some bias in what I choose to write about. However, I will shortly be posting my write-up on Alibaba, which is a personal investment that I made in late July 2021, and which has since gone down by almost 50%. I believe this should put me back in check.

Overview and Investment Pitch

Ovintiv (formerly Encana) is a North American unconventional hydrocarbons exploration and production (E&P) company based in Denver, Colorado. It engages in the production of Oil & Condensate, Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs), and Natural Gas, which represent 36%, 15%, and 49% of its production mix, respectively. In terms of revenues, the company’s Oil & Condensate division accounts for about 50% of revenues, while the NGLs and Natural Gas segments each represent about 25%. Its principal assets are located in the Permian in west Texas, Anadarko in west-central Oklahoma, and Montney in northeast British Columbia and northwest Alberta. Its other non-core upstream assets are located in Bakken in North Dakota and Uinta in central Utah.

Source: 4Q & YE21 Investor Presentation

Note: Released after my pitch and is included here for illustrative purposes only

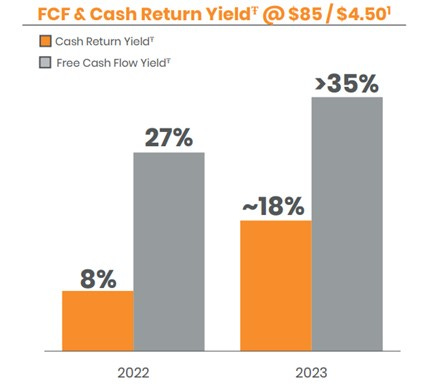

As of the 14th of February, the company had a Market Capitalization of $11.1bn (at $41.67 and 266.4m shares outstanding) and Enterprise Value of $16.9bn. The company stated that it expects to generate ~$10bn and ~$21bn cumulative Free Cash Flow (FCF) over the next 5 years and 10 years, respectively, at $65 WTI oil prices per barrel and $2.75 NYMEX natural gas prices per therm. As I will justify later, I believed such prices levels to be quite a conservative assumption given long-term industry supply-demand dynamics. On an annualized basis, the expected FCF translated to a 5.5x P/FCF, or about a 18% FCF yield. In other words, you could be receiving your money back in a little over 5 years and would still own the remaining assets after this point. (About a week after I pitched the stock, management announced that, based on $85 WTI and $4.5 NYMEX, Ovintiv would be expected to generate FCF of $2.9bn in 2022, or a 26% FCF yield, and that a reduced negative impact from hedges could raise this to >35% in 2023). When compared to the 2.5% yield on the 10-year treasury, and a S&P 500 earnings yield of about 5%, I believed that to be more than an attractive risk-adjusted return. While the company was expected to pay a cash yield (repurchases and dividends) of ~11% at $80 WTI and $4 NYMEX, it was set to increase it to ~21% once the company hits its net debt target of $3bn. According to management, this was expected to happen in 2H 2022. I posited that this would cause investors to pay more careful attention to the stock and would therefore act as a catalyst for a re-rating.

Source: 4Q & YE21 Investor Presentation (Market data as of February 18, 2022)

Note: Released after my pitch and is included here for illustrative purposes only

Ovintiv was also trading at a discount to its peers. As of the 14th of February, it traded at a forward EV/EBIT of 5.8x and a forward EV/EBITDA of 3.9x, versus an average of 7.2x and 4.6x for its peer group, respectively (see charts below). However, given that Ovintiv is one of the lowest cost producers in the industry, I believed that it should trade at a premium. According to Rystad Energy, as of 2020, Ovintiv had an overall break-even price of about $36 per barrel. In fact, its break-even has likely decreased since then. In its Q4 2021 Investor Presentation, the company reported a ~$35/bbl breakeven including its base dividend, which implies a breakeven excluding its base dividend in the low $30s/bbl. To put this into context, the oil majors, such as BP, Shell, Total, and Exxon, have break-even costs that typically range between $40 and $45 per barrel. The lowest-cost shale producers, such as EOG and Marathon, have break-even costs of about $35 per barrel. Such a low-cost base allows Ovintiv to generate above-average returns on capital over the cycle and somewhat insulates it from decreases in the oil price.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Rystad Energy; L.E.K. research and analysis

There are several reasons why I believed this investment opportunity existed. Namely, I believed Ovintiv was trading at a significant discount to its intrinsic value due to 1) a poor track record of capital allocation from previous management, 2) financials which were obscured by hedges and legacy costs that were expected to roll off in the near future, and 3) a general aversion to the oil and gas industry from the part of investors.

Management and Capital Allocation

First, the company has had an awful history of mismanagement and value destruction, which has driven away long-term investors with knowledge of the assets and created for itself a bad reputation. In the early 2000s, Ovintiv (then Encana) was the largest Oil and Gas company in Canada. By 2007, it was producing 3,798 MMcfe/d (representing almost 25% of Canada’s natural gas production) and had a Market Capitalization of more than $50bn. However, over the years, it made a series of “bet-the-farm” acquisitions and divestitures that in hindsight turned out to be extremely poorly timed:

In 2009, the CEO at the time, Randy Eresman, spun-off the company’s oil assets and announced plans to double natural gas production within 5 years. Over the next 5 years, the North American natural gas prices languished, while the price of oil recovered from its post-financial crisis lows.

In 2014, under its newly-appointed CEO since June 2013, Doug Suttles, Ovintiv decided to acquire Athlon Energy for $7.1bn ($5.9bn in cash) and shale assets in Eagle Ford for $3.1bn (in shares). The transactions were made months before the price of oil collapsed due to a price war between Saudi Arabia and US shale producers. The post amble is that the Eagle Ford assets were sold recently in 2021 for only $880m, suggesting that Ovintiv overpaid for them.

In 2018, the company acquired Newfield Exploration for $5.5bn, again, just before oil prices approached their peak and subsequently declined sharply. Management justified a 35% premium for the assets by calling the STACK in the Anadarko Basin a “world-class, oil-rich” play. However, while the industry shortly thereafter recognized the unattractiveness of the basin and began withdrawing from it, Ovintiv continued to dedicate about 30% of its capital to the play.

Altogether, from 2013 to 2021, net debt at the company increased by 53% from $4.6bn to $7.1bn, mostly due to the acquisitions, while the stock fell by more than two thirds. Despite this, the CEO Doug Suttles received compensation of 12.6m in 2019 and $92m over the period. To be fair to Suttles, from 2013 to 2019, he received only 61% of the reported pay due to declines in the value of the long-term incentive awards he was granted. However, this level of compensation still seems unwarranted given the poor experience for shareholders.

Since then, however, a number of key events in 2021 have significantly altered the circumstances for the shareholders of Ovintiv:

In January, Kimmeridge Energy Management, a PE firm focused on low-cost upstream U.S. unconventional oil & gas assets, launched a proxy fight for three board seats and urged the company to alter its capital spending and governance.

In February and March, Ovintiv sold its Eagle Ford and Duvernay assets, using proceeds to pay down debt.

In February, Ovintiv modified the executive compensation program to tie compensation to (i) debt reduction, (ii) relative performance to the S&P and XOP indices, (iii) a ROIC metric, (iv) and methane emissions intensity target.

In March, Kimmeridge added Katherine Minyard to the board. Katherine Minyard is an Investment Principal and Partner at Cambiar Investors, covering energy, metals and mining, industrials, basic materials and utility equities. Before joining Cambiar, she was an Executive Director in the Equity Research Team of J.P. Morgan where she covered a combination of Integrated Oil, Refining, Canadian Oil and US E&P companies.

In August, Doug Suttles stepped down as CEO (seemingly at the behest of Kimmerage) and was replaced by the company’s president, Brendan McCracken, who has been with the company for 25 years.

In September, Ovintiv announced its New Capital Allocation Framework in which it:

Reaffirmed a net debt target of $3bn (to this end, it has already achieved $2.3bn of net debt reduction since 2020 and had net debt of $4.6 as of Q4 2021).

Promised to increase cash returns to shareholders to 25% of FCF after base dividends before reaching its $3bn net debt target and to at least 50% thereafter.

Committed to a long-term reinvestment rate of less than 75% of non-GAAP cash flow at mid-cycle prices, reflecting a strong auto-imposed capital discipline.

Obscured Quality and Profitability

Ovintiv’s financial and operational qualities are obscured by short-term, legacy financial factors. As the effects of these factors diminish over time, they should reveal an asset can distribute large amounts of cash to its shareholders.

First of all, Ovintiv uses hedges primarily to reduce the impact of fluctuations in the price of oil on its ability to service its debt. In 2021, these contracts essentially capped the price it received for its sales oil and natural gas. For instance, in 2021, 88.6% of Ovintiv’s oil sales were capped at between $45.84 and $53.92 and 73.5% of its natural gas sales were limited to between $2.51 and $3.36. Most of these contracts were entered into in 2020 at unfavourable levels when the industry was grappling with the aftermath of the pandemic, and when Ovintiv was struggling with an overly leveraged balance sheet. So far in 2022, it has entered into hedges for 44% of its oil and 81.2% of its natural gas production at maximum prices of about $71 and $2.5-$3, respectively. This will allow it to benefit more from increases in oil prices. According to the company, in 2022 it will generate an additional $365m in FCF for every additional $5 increases in WTI and $130m for every $0.25 in NYMEX. As it continued to reduce its net debt levels, I expected it to continue to wind down the percentage of its production that it hedges.

From 2020 to 2025, Ovintiv will also be eliminating various legacy costs that will contribute an additional $485m to its FCF. Already in 2021, such legacy costs were reduced to $235 due to the roll-off of costs related to the decommissioning of the Deep Panuke natural gas field located offshore Nova Scotia. Additional costs savings are expected to be generated mainly by the expiration of various transportation and processing contracts. According to management, these cost reductions have no execution risk. As they materialise, they further reveal the cost-competitiveness and cash-flow generating potential of Ovintiv.

Aversion to the Oil & Gas Industry

The experience of public market investors in oil & gas over the last decade has generally not been very pleasant, particularly for those who have invested in shale producers. The industry has faced oversupply from the shale boom in the US on the supply-side and ESG concerns from consumers and governments on the demand-side. This has caused investors to shun the industry and has resulted in the weighting of the energy sector in the S&P 500 to decrease from a peak of 15% in 2008 to under 2% in 2021.

The withdrawal of capital from the industry over time has, of course, forced oil & gas companies to reduce their capital expenditures on upstream exploration and production of oil and gas. According to Wood Mackenzie estimates, upstream capital spending in 2020 was roughly 30% lower than in 2019 and 60% below 2014 levels. In 2020 and 2021 global upstream capital expenditures averaged $320-$350bn, roughly 25% short of what is needed to hold production steady at 100 MMb/d, according to Energy Aspects.

Underinvestment has also been a common trend across various sources of energy. Investment decisions to build coal-fired power projects have declined approximately 80% since 2015 from a level equivalent to over 90 GW to less than 20 GW in power generation. By the end of 2022, Germany will have closed down all of its 17 nuclear reactors as part of a plan it has had in place since 2000 to phase out the energy source.

And yet renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and others have not picked up the slack. Global investments in renewable power have only increased by $51bn (17%) from 2015 to 2020, according to the IEA. Costs efficiency and productivity levels of renewable energy sources have increased, meaning that renewable energy generation has increased by just over 1.5 GW (93%). However, this increase is from a relatively small base; fossil fuels still represent 84.3% of global energy consumption whereas wind and solar only represent 3.3%.

Nevertheless, given the recent history of the industry, ‘shale-shocked’ investors are worried that OPEC+ and shale producers will increase production in response to higher prices and flood the market. However, there are signs that shale producers may be unwilling, and OPEC+ may be unable, to significantly increase production. Publicly-listed E&P companies in the US (which represent about 50% of production) have been slow to drill new wells and have preferred returning capital to please investors after years of poor performance. For instance, Pioneer CEO Scott Sheffield has said that “whether it’s $150 oil, $200 oil, or $100 oil, [they’re] not going to change [their] growth plans.” Though the US drilling effort is rising, it must accelerate, or US oil production recovery will stall and potentially fall given steep depletion rates of shale oil wells.

On the other hand, while OPEC+ has increased its production quota by 400,000 b/d per month since August, they have struggled to hit quotas due to under-investment and disruptions. For example, in January, they underperformed their targets by 900,000 b/d. This may be a sign that OPEC+ may not have the spare capacity to significantly increase production and bring down oil prices. The IEA forecasts spare capacity of below 3m b/d by Q2 2022, while Goldman Sachs estimates spare capacity of 1.2m b/d, mostly in Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

I was confident that the oil price would remain significantly above its mid-cycle price over the last 10 years of about $65 per barrel. Further still, I believed that it was quite likely that in the long-term the $65 WTI price assumption on which my investment thesis was based was sound. Over the long-term, the price of oil will tend towards the cost that is incurred by the marginal producer of oil. Based on even the lowest IEA forecasts for oil demand over the next 10 years, demand will remain above 80 MMb/d. This is a level which, according to data from Rystad Energy, incurs a marginal cost of production of roughly $65.

Finally, it was my impression that many of the investors that would be considering investing in the oil and gas sector have been dissuaded from doing so because they believe that they have already missed the boat after the spectacular run that energy stocks had in 2021. In my opinion, this way of thinking is a classic case of anchoring bias. Rather than falling for this trap, I believe that one should do the research necessary to determine whether the company is an attractive investment based on fundamentals. In the case of Ovintiv, I thought that this was certainly the case.

Disclosure: I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article. All content on this newsletter, and all other communication and correspondence from me, is for informational and educational purposes only and should not in any circumstances be considered to be advice of an investment, legal or any other nature. Please carry out your own research and due diligence.

Also, they have met all the criteria to be included into the S&P 500. Just wondering when they will actually be included into the index. Thanks for this informative write-up.